This is adapted from an email from my friend Jessica Kumar who lives in India with her family.

By Jessica Kumar | Twitter: @JessicaKumar_

It’s hard to believe a little over a week ago we were writing from a hotel room in Delhi, trying to get a flight back to our city. Through a lot of drama, stress, and uncertainty we made it back home on the 23rd just in time to get groceries and basic supplies.

On March 24, the Prime Minister of India announced a lockdown for the next 21 days, until April 15. There was only a four hour advance notice given and we are fairly sure it will be extended past April 14. All flights, road transportation, busses and trains are stopped. Everything is closed except for food stalls, hospitals, certain banks, and pharmacies. We are able to walk to nearby shops to get groceries and basic supplies.

We see many friends in the US who are able to go out for walks and bike rides as long as you stay away from people. That’s not the case here. The prime minister used words referring to the religious concept of Laxman Rekha–“An uncrossable line has been drawn across the home of your door.” Although people are supposed to be allowed to go out for groceries and medicine, police are roaming the streets and have been known to beat people who seem to be out for the wrong reasons. Law and order here is something of a fuzzy concept, and people are being driven by fear to stay home.

Since Italian tourists are the ones who brought COVID19 into India, there is paranoia about foreigners. I won’t be going out much, if at all, in the near future, since my presence makes people more uncomfortable and fearful.

The poor and marginalized will be the most deeply affected by this lockdown as about 300 million of them survive on daily wages (no salary.) There is also currently a huge migration of people, mainly from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, who are WALKING from Delhi since their jobs have basically vanished overnight and there is no transportation available. That’s a 620 mile journey! This time is certainly unprecedented in history.

And yet people seem to remain pretty calm here. We are thankful we still have access to groceries and so far we haven’t had any shortages of the essential items. People in India are used to things not going according to plan. School being shut for ten days at a time without notice is something we are used to. Not getting back what were supposed to be “refundable” deposits is something that happens here all the time. Security is relative. Inconvenience is a way of life.

Like many in other countries are asking, we’re also wondering things like “Who will take the garbage out today?” As many of you have heard us describe on our podcast, India is a “make it from scratch” culture. At least in our city, we don’t have dishwashers, canned food, or clothes driers. We usually have house help that assists us with the labor required to keep a basic house running, but since no one is allowed to leave home, we are adjusting to a new way of life which requires several hours a day of physical labor. Most of our days are found in food preparation, cooking, cleaning and making sure our house remains in good order, free of pests and a safe place to shelter for the foreseeable future.

The kids enjoy a combination of helping with housework, coloring, playing on our balcony and bicycling in the house. We are trying to do some educational activities an hour or so a day. Much like everyone else on the planet, our productivity is severely hampered and we are coming to grips with that as the days pass.

Now is not a time for productivity. It is a time for survival.

Now is not a time for productivity. It is a time for survival. @JessicaKumar_ Click To Tweet***

About Jessica:

A global nomad from birth, Jessica Kumar currently lives in India where she and her family are involved in economic development work and small business. She and her husband run a podcast, “Invisible India,” where they talk about scrappy travel, interview interesting people and explore the interactions between East and West through the lens of a cross cultural, interracial couple. Find Invisible India on iTunes, SoundCloud and Stitcher as well as on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. She also writes articles related to cross cultural life at www.globalnomadism.com. Follow Jessica on Twitter @JessicaKumar_ (note the underscore.)

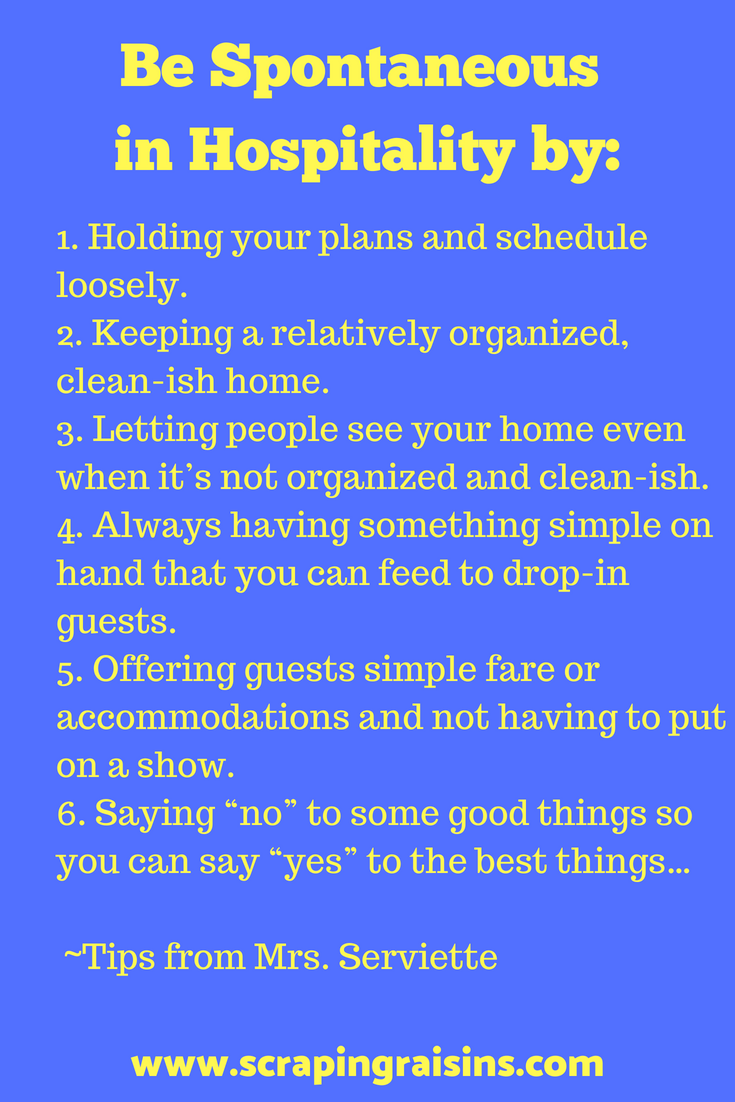

Mrs. Serviette and her husband, Mr. Serviette, are North Americans living in Germany. They enjoy opening their home to people of all different cultures, backgrounds and religions. Their adventures in hospitality inspired Mrs. Serviette to to start her blog, The Serviette, which encourages people to share their tables in a way that bridges cultural and religious gaps, shows creativity, and serves others. Follow her at her

Mrs. Serviette and her husband, Mr. Serviette, are North Americans living in Germany. They enjoy opening their home to people of all different cultures, backgrounds and religions. Their adventures in hospitality inspired Mrs. Serviette to to start her blog, The Serviette, which encourages people to share their tables in a way that bridges cultural and religious gaps, shows creativity, and serves others. Follow her at her  The theme for August is “Homelessness, Refugees & the Stranger,” so send me a post for that, too, if you have a good idea!

The theme for August is “Homelessness, Refugees & the Stranger,” so send me a post for that, too, if you have a good idea!

Mary Grace Otis is a writer, editor, and podcaster who lives with her husband and three boys in northern Michigan. You can find her podcast and posts at

Mary Grace Otis is a writer, editor, and podcaster who lives with her husband and three boys in northern Michigan. You can find her podcast and posts at  We are giving away a copy of

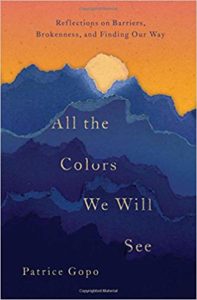

We are giving away a copy of

Patrice Gopo is a 2017-2018 North Carolina Arts Council Literature Fellow. She is the author of All the Colors We Will See: Reflections on Barriers, Brokenness, and Finding Our Way (August 2018), an essay collection about race, immigration, and belonging. Please visit

Patrice Gopo is a 2017-2018 North Carolina Arts Council Literature Fellow. She is the author of All the Colors We Will See: Reflections on Barriers, Brokenness, and Finding Our Way (August 2018), an essay collection about race, immigration, and belonging. Please visit

A Coloradan by birth, Alicia currently lives in Cairo, Egypt with her husband, and three boys three and under. Always a nurse at heart, her impossible 24/7 job these days is keeping her boys alive while trying to learn Arabic, engage with her community, and listen to the stories of the refugees, Egyptians, and expats she is surrounded with. Follow her on Instagram

A Coloradan by birth, Alicia currently lives in Cairo, Egypt with her husband, and three boys three and under. Always a nurse at heart, her impossible 24/7 job these days is keeping her boys alive while trying to learn Arabic, engage with her community, and listen to the stories of the refugees, Egyptians, and expats she is surrounded with. Follow her on Instagram

As a mom, I juggle two different kinds of parenting — long-distance to our 3 adult kids (who are white on the outside but very Chinese on the inside) and our two adopted Chinese boys at home who have special needs. Since being back in the US, my husband has taken up cooking Chinese food, with a specialty of Lanzhou beef noodles (where we used to live and where our boys are from), giving us a taste of “home.” You can follow our story on my

As a mom, I juggle two different kinds of parenting — long-distance to our 3 adult kids (who are white on the outside but very Chinese on the inside) and our two adopted Chinese boys at home who have special needs. Since being back in the US, my husband has taken up cooking Chinese food, with a specialty of Lanzhou beef noodles (where we used to live and where our boys are from), giving us a taste of “home.” You can follow our story on my

Elizabeth Hinnant lives in Atlanta with her husband Neal and a corgi/shepherd diva pup named Heidi. She (Elizabeth, not the dog) writes about science, tech and chronic illness and sometimes tweets

Elizabeth Hinnant lives in Atlanta with her husband Neal and a corgi/shepherd diva pup named Heidi. She (Elizabeth, not the dog) writes about science, tech and chronic illness and sometimes tweets