My children tore into the Christmas boxes yesterday, leaving books, toys, ornaments, lights and wrapping paper strewn about the living room. They arranged the Fischer Price toy manger in bizarre configurations and started in on their own versions of the Christmas story. A week ago for movie night, we watched the kids’ movie, The Star (complete with Oprah, Tyler Perry and Kelly Clarkson as voice actors) on Netflix and I wondered how much of the plot to critique with my children, age six and under.

My children tore into the Christmas boxes yesterday, leaving books, toys, ornaments, lights and wrapping paper strewn about the living room. They arranged the Fischer Price toy manger in bizarre configurations and started in on their own versions of the Christmas story. A week ago for movie night, we watched the kids’ movie, The Star (complete with Oprah, Tyler Perry and Kelly Clarkson as voice actors) on Netflix and I wondered how much of the plot to critique with my children, age six and under.

Should I tell them there wasn’t a man in armor sent to kill Mary and Joseph—or a talking donkey? Or that Jesus wasn’t born in a barn? Should I point out that while the characters in the film looked more Middle Eastern than most adaptations of the nativity (apart from the blue-eyed Mary), their speech and mannerisms were decidedly “Western”? Was it even worth pushing against a story that has morphed into a romanticized version unlike what actually happened two thousand years ago …?

Living overseas and studying culture in graduate school taught me that I often view the world through Western lenses, forming incorrect assumptions as I read the Bible. Yes, the Reformation brought the freedom to study the Bible on our own, but with that comes the mighty weight of responsibility to research the culture behind the text. We can’t just take the Bible at face value and expect to get it right.

As I researched for my book about hospitality from a cross-cultural perspective this past year, I racked up late fines for a book I checked out of the library three times (and finally bought this week). Kenneth E. Bailey spent forty years living and teaching New Testament in Egypt, Lebanon, Jerusalem and Cyprus. The book, called Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes peels away the lenses we’ve used to read the nativity story, confronting our assumptions with truths about Eastern culture.

He says the misinterpretations of the nativity began when an anonymous Christian wrote a “novel” two hundred years after the birth of Jesus. It’s the first fictional account suggesting that Jesus’ birth occurred the very night Mary and Joseph entered Bethlehem. Bailey describes it as “full of imaginative details.” Along with this fictional account, we’ve managed to invent plenty of myths on our own. Here are some I hope to eventually debunk for my children (and myself) as we lug out our Christmas paraphernalia year after year:

Myth 1: No Room at the Inn

Our nativity stories usually involve a dejected Joseph and Mary finally bedding down in the straw of a barn because there was no room for them in the inn. But Bailey writes that “if Luke expected his readers to think Joseph was turned away from an ‘inn’ he would have used the word pandocheion, which clearly meant a commercial inn. But in Luke 2:7 it is katalyma that is crowded …literally, a katalyma is simply ‘a place to stay’… if at the end of Luke’s Gospel, the word katalyma means a guest room attached to a private home (22:11), why would it not have the same meaning near the beginning of this Gospel?”(32, 33)

Bailey points out that most Middle Eastern homes for the past 3,000 years were made of two rooms—one a guest room, and one for the family and their animals. Joseph had likely already arranged to stay at the home of a friend (he knew Mary would be giving birth around then, so of course he would plan ahead–perhaps he’s not as inept as we imagine …). Rather than a story of rejection, the birth of Jesus was, in fact, one of grand hospitality—a family gave up their own room to make space for the holy family.

As proof that Jesus wasn’t born in squalor, Bailey points out that in the spirit of Middle Eastern hospitality, the shepherds would have whisked Mary away to their homes had their accommodations been unacceptable for a baby. As it was, they left them there, deeming the lodging fit for royalty, and raced off to spread the incredible news.

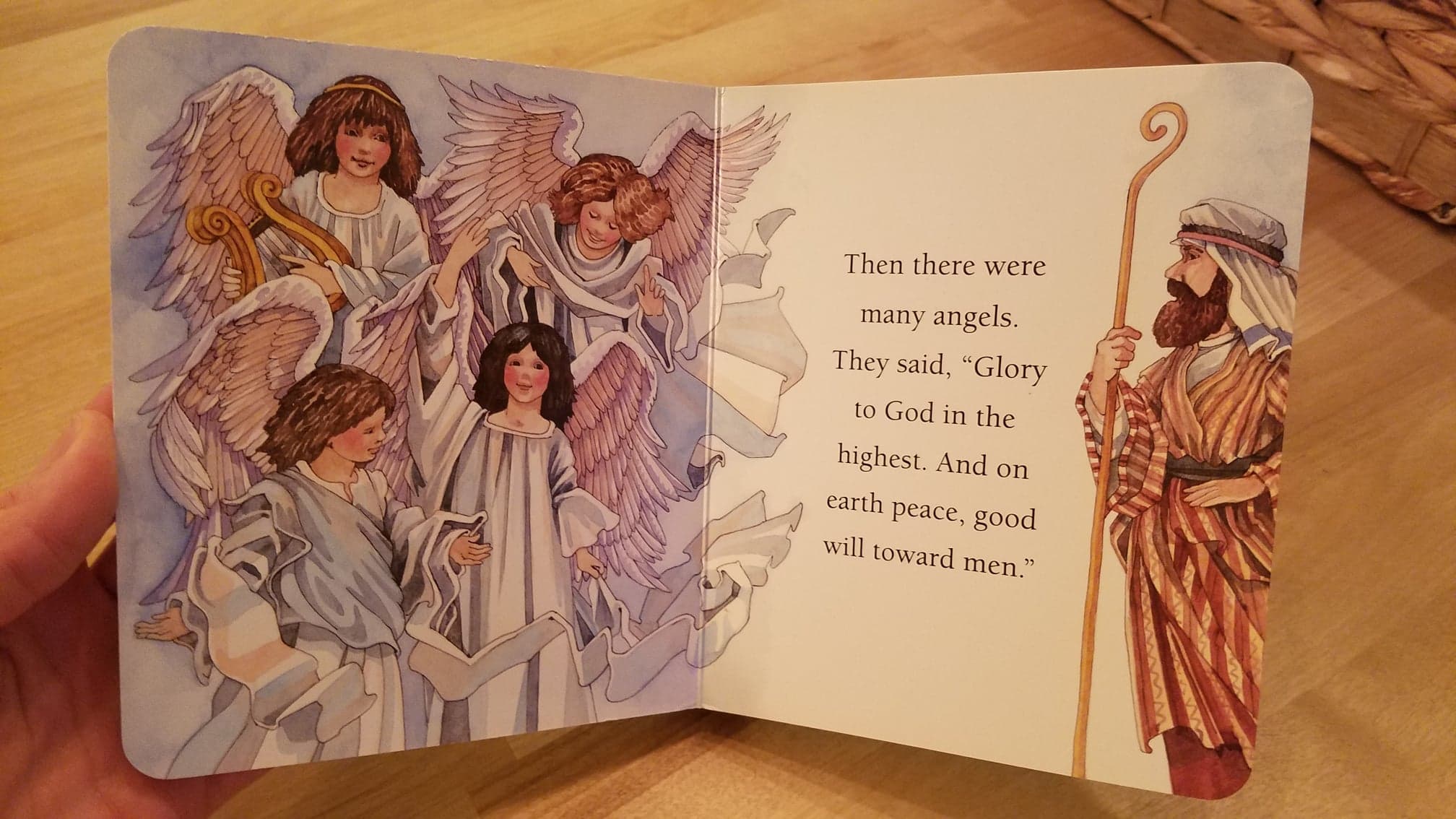

Myth 2: Feminine Angels

For whatever reason, this misinterpretation of the Christmas story really irks me. In the Bible, angels were feared. They were warriors who inspired trepidation and trembling, not cuddling and cooling. Perpetuating the myth of an anemic angel lowers the bar on God’s unnerving power. Every single angel in the Bible is described as male, and most immediately say, “Fear not”—because they were terrifying.

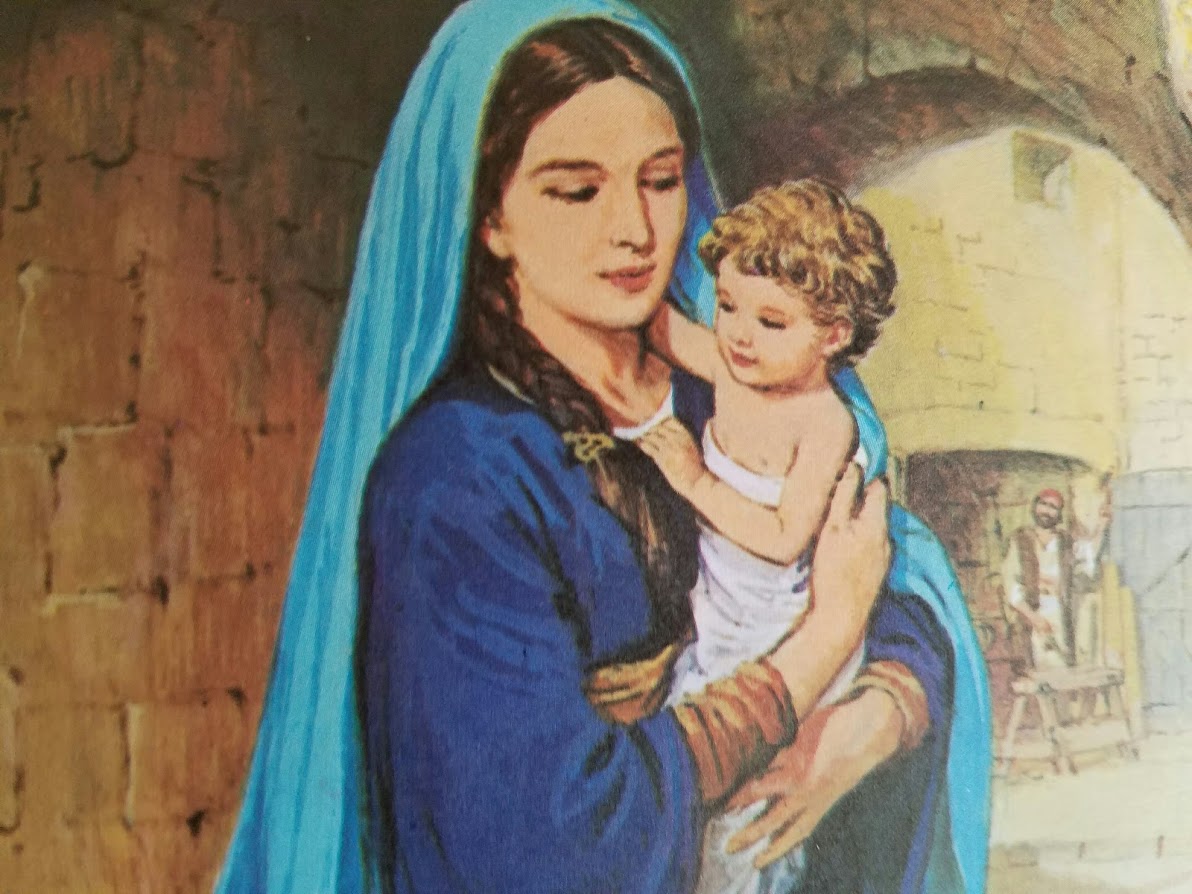

Myth 3: White Jesus

Last year, I rounded up all the toys and pictures of baby Jesus I could find in my home. Most of them revealed a Caucasian, white-looking Jesus. While every culture has depictions of a Jesus who looks like they do, it’s still important to acknowledge that Jesus was born in the Middle East, therefore he most likely had brown skin, brown eyes and dark hair.

Why does this matter? In an article for Christianity Today, author and speaker Christena Cleveland writes, “Not only is white Jesus inaccurate, he also can inhibit our ability to honor the image of God in people who aren’t white.” (While you’re at it, you should follow her on Instagram because her posts lately have been amazing.) Deifying whiteness deadens the broad brush of a God who pigmented all skin and called it “good.”

Images matter. The more we surround ourselves with images of a white Jesus, the more we begin to believe that he was white. (That said, it is very difficult to find nativity sets with a brown Jesus–the Fischer price one we have has only one brown-skinned figure–the shepherd. But I have a few options at the end of this post.)Myth 4: The Timeline

In our carved wooden nativity set, shepherds, donkeys, wise men and sheep crowd around baby Jesus. Most people know about this myth, but Richards and O’Brien in Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes note that, “When the wise men arrived, they went to a house where the toddler Jesus and his parents were living (Mt. 2:11)” (144). The visitation of the wise men occurred years after the birth of Christ, not on the night of his birth. While it’s not wrong to compress the Christmas story for the sake of a play or pageant, it still bears acknowledging that events have been tampered with in our retelling.

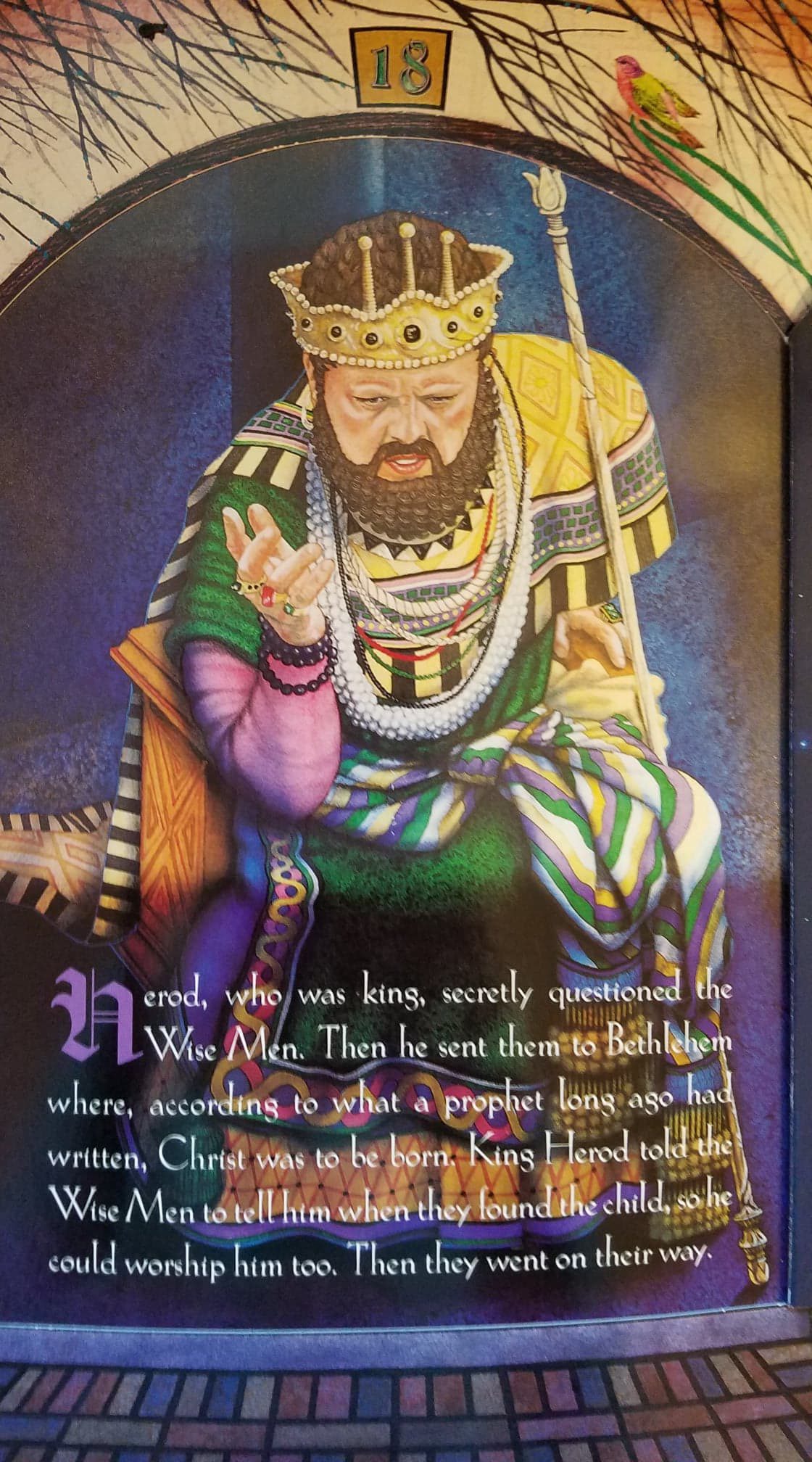

Myth 5: The Omission of Infanticide

This isn’t so much of a misconception as an omission in the story we tell our wee ones. I’m not suggesting we go into this as we light our Advent wreathes and eat cookies as a family, but like so many of our Bible stories, I think we’re in danger of desensitizing ourselves and our little ones to violence when we gloss over murder, rape, genocide, torture, and abuse in our common Sunday School Bible stories. Amazon offers a startling disclaimer for the children’s Adventure Bible: “As with any full Bible, in the context of Scripture there is frank mention of drunkenness, nudity, and sex that parents may not expect to see in a children’s edition.”

As adults, we grow so used to the familiar tales that we forget to be shocked, horrified or to even to acknowledge the sickening violence. The story of the birth of Jesus is no different, as Herod slaughtered innocent children in his rage at the coming king. Bailey says “there appears to be a conspiracy of silence which refuses to notice the massacre. Why then does Matthew include it?” (58) He suggests that “if the Gospel can flourish in a world that produces the slaughter of the innocents and the cross, the Gospel can flourish anywhere” (59). Perhaps as adults we need to meditate on the violence and allow ourselves to absorb the horror as a way of recognizing God’s presence in suffering.

Myth 6: Mary Was an Unwed Mother

Most Americans read “betrothed” and incorrectly assume it means the same thing as “engaged.” In reality, under Jewish law, Mary and Joseph traveled to Bethlehem as fully married couple who had not yet consummated their marriage. The Middle Eastern view of betrothal bears little resemblance to our conception of engagement in the West.

Myth 7: Mary and Joseph Were All Alone

My Chinese students could never understand why I wanted to be alone–because they never were. In fact, most non-Western cultures are collectivist and can’t understand the individualism of those of us in the United States and parts of Europe. Our Saudi international student said even her 12 year old sister still slept in her parents’ room, an example that holds true in many Middle Eastern cultures. Why would Mary and Joseph have been any different?

As they were traveling back to Bethlehem to register, Bailey points out that most homes would have been available to Joseph, who was of the royal lineage of David. To reject someone of that heritage would bring shame and humiliation to the community. Mary, too, had relatives in the area and had just been visiting her cousin Elizabeth not far away in the “hill country of Judea.” Bethlehem was in the center of Judea. They were not friendless in Bethlehem.

The birth in the family room of a friend’s home would have been attended by other women and midwives as tradition dictated. Far from alone, Mary and Joseph would have been surrounded by more help than they needed. (My friend, Sarah Quezada, is sharing more about what she’s calling “the Advent caravan” the next three Sundays, you can sign up for that here.)

Myth 8: The Boot-Strapping Holy Family

In America at least, many of us love the Cinderella stories of the underdog rising to power. The United States lauds those who pull themselves up by their bootstraps, forge ahead without the blessing or need of others and make something of themselves. I wonder if this love of independence and individualism has seeped into our telling and retelling of our beloved nativity story. We love the idea that an unwed family left home and made something of themselves in spite of rejection. Not needing anyone else, they gave birth alone in a barn to the audience of only animals.

But what if we changed the narrative to reflect the culture in which it was written? A culture that valued hospitality, relationship, togetherness and family? How would this alter our tale?

***

Why does all this matter? The more I learn about other cultures, the more I realize how much of my own culture I project onto my personal reading of the Bible. Understanding the nuances of stories in the Bible from the perspective of the culture in which it was written fills in the gaps of our shallow, faulty understanding.

I know there are resources out there that offer a more accurate nativity story. In our family, we use the Advent book and the Jesus Storybook Bible to share the Christmas story with our little ones, though these also fall short.

I want my children to peel away the heroics and white-washed Bible stories to see the God behind the myths. Mostly, I want my kids to know the many dazzling facets of God they’re missing when they settle for a Western god made in their own image.

***

Resources:

The Story of Christmas (recommended by a friend of a friend)

The Story of Christmas (recommended by a friend of a friend)

Olive Wood Miniature Nativity Set (we have this one–it’s small and not for play, but nice!)

Olive Wood Miniature Nativity Set (we have this one–it’s small and not for play, but nice!)

Nativity Sets from Peru (this site looks awesome–they have sets from all around the world!) This mini one from Peru is $16.99.

African American Nativity for $54.99

Bark Cloth Nativity Set for $29.99

Bark Cloth Nativity Set for $29.99

Painted Peg Doll Nativity Set for $40 (Looks more Middle Eastern, but still has a female angel…)

Painted Peg Doll Nativity Set for $40 (Looks more Middle Eastern, but still has a female angel…)

Diverse Peg Doll Nativity Set for $142 (more money if you order the Dr. Who character!!!…???)

Diverse Peg Doll Nativity Set for $142 (more money if you order the Dr. Who character!!!…???)

***

For December, the theme on the blog is “The Other Side of Advent.” Let me know if you’re still interested in guest posting (I’m usually willing to extend deadlines)! Check submission guidelines here.

For December, the theme on the blog is “The Other Side of Advent.” Let me know if you’re still interested in guest posting (I’m usually willing to extend deadlines)! Check submission guidelines here.

Sign up for the (occasional) Mid-month Digest and the (loosely) “end of the month” Secret Newsletter for Scraping Raisins Here:

Follow me on Instagram @scrapingraisins–I frequently give away books and products I love!

**This post includes Amazon affiliate links.

I am Kaitlin Sara Ho Givens, also known as “Kata.” I am a Chinese-American campus minister focusing in planting new movements, empowering leaders, and raising up purposefully multiethnic, reconciling communities that reflect the heart of God. I am pursuing a Masters of Divinity at Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary. I hold a Bachelor’s degree in English from Boston University. I speak Spanish and French and Minion proficiently, with Greek and Hebrew up next.

I am Kaitlin Sara Ho Givens, also known as “Kata.” I am a Chinese-American campus minister focusing in planting new movements, empowering leaders, and raising up purposefully multiethnic, reconciling communities that reflect the heart of God. I am pursuing a Masters of Divinity at Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary. I hold a Bachelor’s degree in English from Boston University. I speak Spanish and French and Minion proficiently, with Greek and Hebrew up next. Sign up for the Scraping Raisins newsletter by midnight (MT) February 28th and be entered to win a copy of

Sign up for the Scraping Raisins newsletter by midnight (MT) February 28th and be entered to win a copy of

Dr. Yabome Gilpin-Jackson considers herself to be a dreamer, doer and storyteller, committed to imagining and leading the futures we want. She is an award-winning scholar, consultant, writer and curator of African identity and leadership stories. She was born in Germany, grew up in Sierra Leone, and completed her studies in Canada and the USA. Yabome was named International African Woman of the Year by UK-based Women4Africa and also won the Emerging Organization Development Practitioner by the US-based Organization Development Network. Yabome, who is married and the mother of 3 children, has also published several journal articles and book chapters and continues to research, write and speak – most recently at Princeton University – on the importance of holding global mindsets and honouring diversity and social inclusion in our locally global world.

Dr. Yabome Gilpin-Jackson considers herself to be a dreamer, doer and storyteller, committed to imagining and leading the futures we want. She is an award-winning scholar, consultant, writer and curator of African identity and leadership stories. She was born in Germany, grew up in Sierra Leone, and completed her studies in Canada and the USA. Yabome was named International African Woman of the Year by UK-based Women4Africa and also won the Emerging Organization Development Practitioner by the US-based Organization Development Network. Yabome, who is married and the mother of 3 children, has also published several journal articles and book chapters and continues to research, write and speak – most recently at Princeton University – on the importance of holding global mindsets and honouring diversity and social inclusion in our locally global world.

This month we’re discussing racism, privilege and bridge building. If you’d like to guest post on this topic, please email me at scrapingraisins(dot)gmail(dot)com. Yes, this is awkward and fraught with the potential for missteps, blunders and embarrassing moments, but it’s necessary. Join me?

This month we’re discussing racism, privilege and bridge building. If you’d like to guest post on this topic, please email me at scrapingraisins(dot)gmail(dot)com. Yes, this is awkward and fraught with the potential for missteps, blunders and embarrassing moments, but it’s necessary. Join me?

Vannae is pastor and lives with her hubby and daughter in Colorado. She is passionate about justice and loves to help the voiceless find their voice. Vannae enjoys spending her time creating, and can often be found writing, or creating new recipes in her kitchen.

Vannae is pastor and lives with her hubby and daughter in Colorado. She is passionate about justice and loves to help the voiceless find their voice. Vannae enjoys spending her time creating, and can often be found writing, or creating new recipes in her kitchen.